In celebration of Earth Month at Black Women for Wellness, we are honoring the life and legacy of Hazel M. Johnson, who blossomed into the Mother of the Environmental Justice Movement.

Early Life

Hazel’s story begins at Cherokee Hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana. On January 25, 1935, she was born Hazel M Washington from Mary Nee Dunmore and Clarence Washington.

Her family lived near the Gulf Coast of Louisiana which is now known as Cancer Alley. Today, this is an 85 mile-long stretch of petrochemical facilities along the Mississippi river — a quarter of all such facilities in the United States.

With megapolluters not far from Hazel’s backyard, it’s possible this relates to how alarmingly death moved through her family. Of four children, Hazel was the only one to make it to adolescence.

Then and now, the communities within Cancer Alley are predominantly made up of Black and low-income residents, and the concentration of 200 hazardous operations in this area has consistently produced the highest risk of cancer from industrial air pollution in the country.

Residents have endured a range of reproductive health issues, respiratory ailments, and various cancers. Because this land was previously home to numerous plantations, many consider the placement of these toxic facilities as a continuation of enslavement – same beast, new form.

Neighboring communities like Hazel’s saw their health affected greatly. After her father passed away, her mother followed, so by 12 years old, Hazel was an orphan.

Hazel went to work at an industrial laundry facility for a local hospital, and due to the hazardous conditions, she contracted tuberculosis. In her youth, Hazel experienced the realities of environmental racism even if there wasn’t yet a term for this reality.

In 1949, Hazel moved in with her aunt in Los Angeles where she attended Jefferson High school. This was an era when the city would’ve bustled with life as tens of thousands of African American migrants moved West to seize work opportunities.

The industrial workforce was booming as businesses sprung up to support the country’s war effort during World War II.

It was around this same time that her future home, Altgeld Gardens in Chicago, was being built to house Black veterans returning home from the brutal realities of a world war.

After Los Angeles, Hazel moved back to New Orleans to live with her grandmother, and during her time at home, she met her husband-to-be while working at a large produce company.

Hazel Washington became Hazel Johnson when she married John W. Johnson Sr. in 1955. Shortly after, John and Hazel became parents to two children, and eventually, the two grew to seven.

Becoming ‘Mama Johnson’

In 1956, The Johnson family relocated to Chicago. The veteran status of Hazel’s brother allowed them to move into Altgeld Gardens in 1962.

After seeing the community while visiting family multiple times before, she fell in love with it right away, calling it “the most beautiful place she had ever seen.”

The buildings sported a mid-century modern style of architecture which was considered cutting edge for its time. Hazel’s very own husband, John Johnson, helped build one of the school buildings at Altgeld.

Overall, the structures were designed with veterans in mind as the community’s look took after other bases and veteran communities. This allowed residents to forge a close-knit community, provide local social services, and establish a sense of safety.

Sadly, Hazel’s new start took a tragic turn with the untimely death of her husband John at only 41 years young. John was considered a lively man who joked with his kids about their scuffles at school and helped build the home she’d grown to love.

The event was as jarring as it was peculiar because John was a generally healthy young man who rarely smoked – contracting and dying from lung cancer didn’t make sense.

And he wasn’t the only one who suffered. Her children developed skin and lung issues, and others in the community reported similar symptoms.

This led Hazel to search for an answer. Her research led her to watch a 1970’s TV program about environmental-related cancers. When she tried to get more information about the origins of the health trends in Altgeld Gardens, the first agency she turned to was the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

However, at a time where the EPA’s only purpose was to (poorly) regulate industries and partner with academic institutions, they offered her no help. Hazel proceeded to call other agencies, organizations, academics, and activists who were able to provide her with books, research papers and other materials.

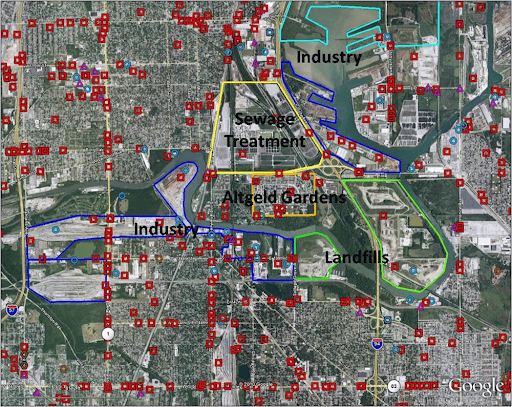

As the papers cluttered and covered her living room floor, the picture of Altgeld’s polluted land and neglected people came into clearer focus. The beloved community, Altgeld Gardens, was encompassed by what she referred to as a “Toxic Doughnut.”

Dozens of waste sites surrounded and poisoned Altgeld residents with a variety of untreated chemical compounds that contaminated the air, soil, and water, and Altgeld Gardens itself was built on a former industrial waste dumping ground. With little to nothing being done about it, she took matters into her own hands.

Hazel campaigned and won a seat on the Altgeld Gardens Local Advisory Council. While this marked a tremendous jumping off point for her environmental justice advocacy, this was certainly not the start of her activism.

She previously worked as a canvasser for the South Side residential group, The Woodlawn Organization, which addressed community health concerns, segregated housing, and other issues. She also worked for a non-profit advocating for children with developmental disabilities now known as The Arc.

Finally, Hazel helped the mayoral election campaign of the Harold Washington, whose legacy of people-centered policies still has an impression on many Chicago residents today. On top of that, Hazel had been a known contributor to Altgeld’s mutual aid networks since her arrival in the neighborhood.

With this experience and her growing wealth of knowledge, residents had no problem voting ‘Mama Johnson’ into her seat; they saw how much Hazel would bring to the Council’s table.

Unfortunately, the Council, despite Hazel’s pushes, failed to directly address the rampant infrastructure deterioration in Altgeld at the time.

Once again taking matters into her own hands, she formed People for Community Recovery (PCR) in 1979. It was officially incorporated as a not-for-profit organization on October 25th, 1982.

That first year, PCR advocated for asbestos, PCB, and fiberglass removal, lead abatement on public housing units, a ban on new or expanded landfills in Chicago, and extending the area’s water and sewage services to neighboring Chicago communities.

The movement proliferated throughout the city as PCR later forged a coalition: Citizens United to Reclaim the Environment (CURE). CURE housed a team of 5 local grassroots organizations that leveraged their collective power to push back against city and state officials who wanted to issue another permit to a toxic waste company nearby.

After several negotiations, when the officials issued the permit anyway, Hazel and the crew took to the streets. Hundreds of protestors turned out to block 57 trucks from dumping several tons of toxic waste near their community.

They successfully delayed the operation for over 5 hours before Hazel and other protestors were arrested. Ultimately the landfill never opened and the city finally placed a moratorium on additional waste sites in the city.

—

Notably, this model of coalition building to achieve collective wins is one that environmental justice communities still employ around the world.

Black Women for Wellness is part of coalitions to address neighborhood oil drilling, the lifecycle of plastics pollution, the maternal mortality rate for Black women, and more. Hazel’s story provides lessons for all of us today.

—

Around the same time she founded People for Community Recovery, Hazel began mentoring college students. Chief among them was her young daughter, Cheryl (who we’re interviewing for our Podcast at BWW), and a young Barack Obama.

As a director of the Developing Communities Project, Hazel helped Obama gain traction with residents over the fight to remove asbestos from Altgeld.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of People for Community Recovery

Hazel’s wisdom soon spread worldwide.

In 1991, she was invited to the first National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in Washington, D.C. The summit facilitated the collaborative efforts of EJ activists of color by combining forces, minds, and resources from all across the world.

According to those in attendance, even in a room full of such stellar community leaders, Hazel stood out as a person many of them looked up to. Just as she voiced her excitement to commune with so many faces and people like hers, the feeling was more than mutual.

Her work made many of them feel seen and with her extensive experience, her visibility and mentorship was described as maternal to many younger activists. It was after this summit that she would officially be recognized as the Mother of Environmental Justice.

It emphasize the gravity of this milestone, it is important to recognize that at this time, ‘environmental justice’ wasn’t a widely recognized term, and the work and values of environmental justice activists was quite different from those of mainstream environmentalists who often lacked an equity perspective.

Such environmental activists typically focused on lobbying for land conservation, animal rights, general pollution and other efforts that tended to come from top-down, White-led organizations who hailed heroes like John Muir, and writers like Aldo Leopold.

There failed to be an intersectional lens to address the realities of this country’s history of genociding and displacing Indigenous people, and brutally enslaving Black people, as well as how that history morphed into environmental racism where BIPOC people are sacrificed for industrial gain, while simultaneously excluded from economic opportunity.

Without consideration for these truths, the so-called ‘radical environmental activism’ of the 20th century did not uplift Hazel’s community, or the hundreds of others around the world like hers.

Meanwhile, the Environmental Justice movement has always centered those most harmed by current and past structural racism, namely, Black, Brown, Indigenous and low income communities.

Frontline communities, or those who have been forced to live near toxic land uses, are the beating heart of the EJ movement, and it is Hazel M Johnson who helped create the advocacy roadmap that activists today still abide by.

The divide between these groups was so great that various environmental justice leaders at the time wrote a letter to the 10 most prominent environmental groups urging them to expand their definition of the environment and realize the struggles faced by communities of color battling environmental racism.

Indigenous communities and women of color have always fought for what we now understand to be environmental justice, but looking back, academics and activists attribute the start of the US environmental justice movement to 1982.

The mostly Black community of Warren County, North Carolina came together and organized a massive sit-in of over 500 protestors to block construction of a PCB landfill. This event marked a shift because communities across the Country began to more clearly note the connection between where public officials were placing toxic sites and the demographics of the nearby communities.

To emphasize and document these concerns, Dr. Robert Bullard produced a report that documented locations of municipal waste facilities in Houston. Titled, “Solid Waste Sites and the Black Houston Community” (1983), the study revealed a distinct concentration of toxic waste sites near Black neighborhoods, which constituted the first comprehensive account of environmental racism.

This study was replicated by the General Accounting Office that same year, which confirmed Dr. Bullard’s claims. The United Church of Christ Commission on Racial Justice (UCC) followed up with their own study as well, “Toxic Waste in the United States” (1987).

The profound effect that Dr. Bullard’s study had on expanding the scope of environmental research has earned him the title, Father of Environmental Justice.

Hazel’s efforts produced a founding document as well. While collaborating with a cohort of activists from the 1991 Summit, Hazel Johnson helped distill the values and attributes of the Environmental Justice movement into 17 principles that would shape the language used by EJ activists for years to come.

Environmental and Reproductive Justice

Here at Black Women for Wellness, we celebrate both Earth Week and Maternal Health Week during the month of April. As an organization deeply invested in the reproductive health of Black women and femmes, we want to highlight the intersections between Environmental Justice and Reproductive Justice.

As shared above, Indigenous communities and people of color have been fighting for and protecting basic human rights of women for a long time. It is on the shoulders of these people that the reproductive justice movement was founded.

In June of 1994, a group of Black women, including Loretta Ross, whose experiences were not being captured by the mainstream feminist movement of the time, coined reproductive justice as a holistic, human rights framework.

This framework has 4 tenants, well-defined by Sistersong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective “as the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”

This definition highlights that reproductive justice is not possible without environmental justice and vice versa – truly, we all deserve to live in safe communities.

Looking again towards Hazel’s story, while the impact of pollution in Altgeld Gardens is often demonstrated through the extreme and frequent respiratory harm, the effects of the contamination can be seen through infant and maternal health trends as well.

One of the local pollutants, Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB), has been known to increase the likelihood of various cancers, including breast cancer. It has disrupted hormonal cycles, menstrual cycles, and sperm counts.

Additionally, pregnant people exposed to this chemical before or during their pregnancy have seen newborns with major neurological and motor control issues.

The situation was so drastic that it compelled the efforts of Dr. Gloria Jackson Bacon who was fired from a medical facility in Altgeld in 1968 for speaking out against its subpar healthcare offerings.

Two years later, Bacon opened her own not-for-profit clinic, where she worked tirelessly to establish and expand reproductive services and decrease the infant mortality rate in Altgeld.

The infant mortality rate was around 50.2 deaths per 1000 live births when she first began work in Altgeld. As of 2022, it has decreased to 33.7 deaths per 1000 live births, though it still continues to be about 3 times higher than the rest of the state.

Ultimately, Environmental Justice and Reproductive Justice are interconnected struggles, especially in BIPOC communities that experience the brunt of the climate crises and environmental hazards. If you’d like to learn more, take a look at our Black Maternal and Infant Health program as we fight for systemic changes that produce better health outcomes.

Environmental and Reparative Justice

During Earth Week, Black Women for Wellness will also highlight Reparative Justice, a framework that emphasizes structural change and healing as a means to deliver justice to those who are harmed. Its 3 principles are:

- Stop the harm

- Close opportunities and loopholes to reproduce harm

- Repair and pay reparations to harmed communities

These sentiments appear in Environmental Justice as well. This can be seen in the definition PCR provides, “the principle that all people and communities are entitled to the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards and equal access to the decision-making process to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn, and work.” They also appear throughout the 17 EJ principles.

While Reparative Justice provides a useful guide for offensive parties who want to make amends, it can be useful to advocates and community members as well. We’ll present examples of this in action on our instagram this Earth Week April 22-26th, 2024. Stay tuned and check us out @bw4wla!

Engaging with this work often requires us to clean messes we didn’t make and combat systems we didn’t build. But with the power of compassion and collective action, we are capable of ushering in the future that we want to see. This is one of the many lessons clearly embodied by Hazel’s story and the organization she founded.

Get Involved

If you’d like to support more of this work from People for Community Recovery, you can learn more on their website.

If you’d like to support similar work we’re doing here at Black Women for Wellness, check out the resources and projects detailed on the Environmental Justice page of our website.

We’ll leave you with some parting words from the Johnsons:

“Living in your own shoebox is better than living in anybody else mansion. But you have to take care of your own shoebox so you can continue living in it.”

– Hazel and Cheryl Johnson